WHO WERE THE SINDHWORKIS

Sindh was famous for its hath jo hunar (handicrafts) – printed and embroidered materials, silks, fine cotton and muslins, silverware, lacquerware, furniture, carpets, pottery, handpainted glazed tiles, and jewelry. The Sindhi Hindu traders and merchants that sold this work were called Sindhworkis. Most Sindhworkis were from the Bhaiband community (Bhaiband means brotherhood – this was a traditionally trading community of Sindh) from in and around Hyderabad, and some from Shikarpur and Sukkar. Others were from the Amil community (the educated community of Sindh that knew Persian and English language and worked for the government). They traded not only in handicrafts from Sindh, but also sourced goods from other parts of India, China, and Japan.

The Sindhworkis had international trading companies in far-flung parts of the world, and the trade brought a lot of wealth . Soon young men from the families of these communities began to work for them. Due to long periods of separation from their homeland, the Sindhworkis lived a life that was unique to them and their families.

THE ACCOUNT OF A SINDHWORKI FAMILY

Mrs. Rajshree M. Mulchandani, my mother-in-law, was brought up in such a household. Her father, Bhai Metharam Mohinani, worked for Chellaram Company, a prominent Sindhworki company for forty years. Later on, he went on to become a prominent member of the Sindhworki Bhaiband community. Such was the clout of the community in the social and political arena due to its widespread network, that the then Prime Minister, Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru, met Bhai Metharam when he worked as the senior manager of Chellaram Company, in Nigeria. Here is her account of her childhood in a Sindhworki family and the subsequent exodus of the family from Sindh during the Partition.

THE LIFE OF A SINDHWORKI

“The lives of the Sindhworkis was not easy. They had to work long hours. The firms provided them with food and housing. There would be groups of colleagues working and living in dormitories. Common food was cooked for all the staff, and they would eat together. They had to work abroad for three or four years at a stretch and missed the pleasures of family life. The early Sindhworkis traveled to Colombo, Rangoon, Hong Kong, Penang, Malaysia, etc. After the opening of the Suez Canal, they ventured to Africa and European countries.”

“My father was a Sindhworki. He was a schoolboy of fifteen when he married my mother. Since the responsibilities of running the house fell on his shoulders at sixteen, he took a job in Colombo. He came home every three or four years. He was not present when I was born. One fine day, I saw my mother very happy and excited. All the relatives had gathered in our house. I could not understand what the excitement was about. Then my father entered the house. I stood in a corner wondering who the stranger was. One of my father’s sisters took me and introduced me to him. Thus, I met my father for the first time at the age of three. He picked me in his arms and kissed me.

I did not like him at first. I thought he had usurped my mother’s love and attention from me. But gradually, he won me over with toys, outings, and love.”

“The life of a Sindhworki was that of separation and loneliness. Living away from each other was not easy for both husband and wife. My father always yearned for home-cooked food and missed the joy of family life.”

“Some Sindhworkis got involved with women abroad. Thus, some had two wives – one in Sindh and one abroad. They had children from both wives. The Sindhi wives were often unaware of such a dalliance. But things came to a head during partition when these husbands had to leave Sindh and had to bring in the second wife into the picture. However, a few Sindhi wives accepted the other woman in their lives, and the two coexisted harmoniously.”

THE WIVES OF SINDHWORKIS

“Life for the wives back home was dull and boring. They had to toil for hours under the mother-in-law’s hawk eye. They looked forward to the homecoming of their husbands from foreign lands as only then would they have a chance to enjoy life. The Sindhworki husbands showered their families with love and expensive gifts when they came home.

I remember my mother always cooking in the kitchen, looking after the needs of a large joint family. When I was around three years old, we moved away from the joint family to live in our own house. My father had found a better high paying job by then. Life eased a little for my mother.”

THE PARTITION OF INDIA

“Life in Sindh before partition was peaceful. Hindus and Muslims had no problems with each other. We celebrated our respective festivals and religious ceremonies in harmony. When the partition of India was announced, there was an atmosphere of fear and unrest. The Hindu families had to make plans for the immediate future. Decisions had to be taken regarding where to settle down after leaving Sindh. It was heart breaking for the Hindus to leave their homes and move to new destinations. Children were forbidden to leave their houses. Schools were closed. Our neighbours started leaving the country one by one. My mother was frightened to be left alone in the neighbourhood. One day, a group of Muslim men entered our house. My mother panicked in fear. They assured her that they had no intention of harming us. They just wanted to pick up some furniture, and anything which they fancied. After all, we would be ultimately leaving everything behind. They took away my beautifully carved pingo (swing), and my radio gifted to me by my father.“

“Finally, we left most things behind and left for Karachi. We stayed at my maternal grandparents’ house. We formed a group of relatives and others whose destination was West Africa to go together in a chartered plane. My father was stationed at Freetown, West Africa at that time, where we lived for seven years. In the featured image at the beginning of the article, Bhai Metharam and his wife, Sita Devi(the couple in the center) are seen with Sindhworki staff in Freetown. Other Sindhworki families took off to destinations they worked at such as Hong Kong, Gibraltar, and so on. Some shifted to Bombay for good. Wherever they went, they carried their Sindhi roots along with them.“

FIVE FACTS ABOUT SINDHWORKIS

1. According to Diwan Bherumal in Sindh je Hindun jee Tareek 1946, Sindhworki Bhaibands remitted over rupees two and a half crores from overseas to Hyderabad every year. Remittances by Shikarpuris were in addition to this.

2. The Sindhworkis set up commercial empires from Japan, Singapore, Jakarta in southeast Asia, Ghana, Nigeria in Africa, Gibraltar, Spain in Europe, to Brazil, Suriname, Panama Islands, Chile in South America, to name a few places.

3. The Sindhworkis played a major role in the freedom struggle of India against the Britishers. They donated large sums of money and ornaments to support the Gaddar Movement of Punjab and the Independence movement of Netaji Subash Chandra Bose against the Britishers. In The Sindh Story, K.R.Malkani points out, “When Subhash Chandra Bose set up INA in the Far East, his best and biggest supporters were the Sindhi businessmen there. Both Subhash Bose and Gandhiji referred to Sindhis as “World Citizens” since they are to be found everywhere.”

4. The Sindhworkis were great philanthropists. They endowed several hospitals and colleges to cities like Bombay. They also supported and financed the local communities in their adopted countries.

5. The travels of the Sindhworkis influenced the food back home. Macaroni pasta, china grass, jellies, custards, and pies became part of Sindhi food.

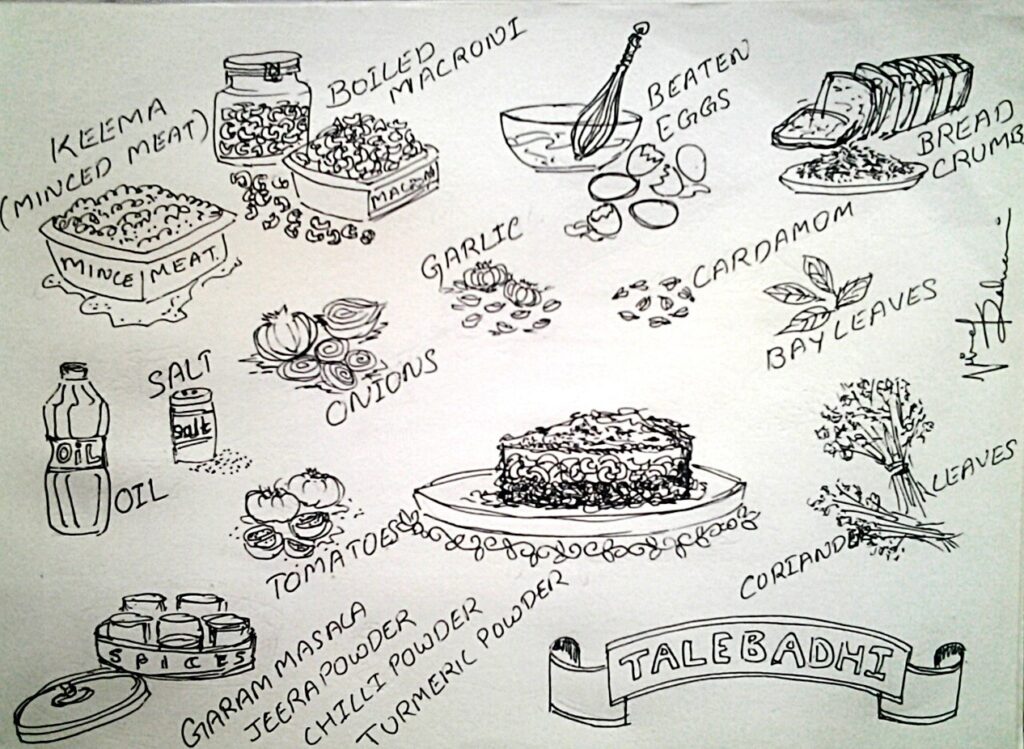

SINDHI TALEBADHI – The Minced mutton and macaroni pie

Talebadhi is a keema (minced mutton) macaroni pie, unique to the Bhaiband community. During their travels abroad, Sindhis picked up ingredients from the countries they worked in and made it a part of Sindhi cuisine. Macaroni pasta is one such delicacy they incorporated in their food and made the dish, Talebadhi. This recipe uses minced mutton, though a vegetarian version can be made using soya granules. My mother-in-law uses leftover Sindhi keema for the dish.

RECIPE

Ingredients

For the keema

Minced mutton – 500 gm

Chopped Onions – 3- 4

Chopped Tomatoes – 2 – 3

Chopped Chillies – 2 – 3

Ginger paste- 1 tbsp

Garlic paste- 1 tsp

Black cardamoms- 2

Bay leaves – 2

Coriander powder- 2 tbsp

Jeera powder – 1 tbsp

Garam masala – 1 tbsp

Turmeric powder – 1/2 tsp

Chilli powder – 1 tsp

Salt – to taste

Oil for cooking

Other Ingredients

Boiled Macaroni – 1 cup (100 gm)

Eggs – 4

Coriander leaves for garnishing

Breadcrumbs (optional)

Procedure

A good mutton keema needs to be sautéed a lot, which we call ‘to bhuno’. Bhuno the mince well at each step to get a flavoursome keema.

- Heat oil in a pan. Add chopped onions. Fry till golden brown.

- Add the cardamoms and bay leaf. Fry for a minute.

- Add ginger-garlic paste and green chillies. Sauté for a minute. Add the mince and salt. Keep on stirring the mince, so it doesn’t stick to the pan. Cook till dry.

- Add tomatoes and the masalas.

- Sauté well. Add a little water and cook the keema on medium heat till the oil separates.

- Let the keema cool.

- Meanwhile, beat the eggs in a bowl with salt. Divide into two parts.

- Assemble the keema, boiled macaroni, and one-half of the beaten eggs in a greased baking dish.

10. Spread the remaining beaten egg mixture on top.

11. Garnish with coriander leaves. My mother-in-law adds breadcrumbs on top to make a crisp layer.

12. Bake at 180o F in a pre-heated oven for 20 minutes till the top is golden brown.

Serve it with bread and soup to make a complete meal or use it as a side dish.

Personal account of Mrs. Rajshree Mulchandani

Recipe by Mrs. Rajshree Mulchandani

Featured Image: Bhai Metharam and Sita Devi with the Chellaram Company staff in Freetown

Featured Image Credit: Personal Collection of Mrs. Rajshree Mulchandani

Jyoti Mulchandani

Ahmedabad

Give a Reply