I was always under the impression that all the Hindu Sindhis left Pakistan in 1947 during the partition and came to India. I now know better as I came across many Sindhi Hindus who came much later after partition or decided to stay back in Sindh forever.

My dear friend, Meena Jagwani’s husband, Mr. Santosh Tolaram Jagwani came from Sukkur district, Sindh, in 1976 when he was 15 years old. I had a freewheeling chat with him about his memories of Sukkur and Sadh Belo, the food, clothes, furniture, and utensils of Sindhis.

For a better understanding of the nostalgic trip to Sindh with Mr. Jagwani, here is a little information on Sukkur.

Sukkur, on the western bank of the Sindhu river, is the third-largest city of Sindh. The historic city of Rohri, a prosperous city of its time, lies directly across Sukkur and is connected by Lansdowne Bridge over river Sindhu built by the British in 1862.

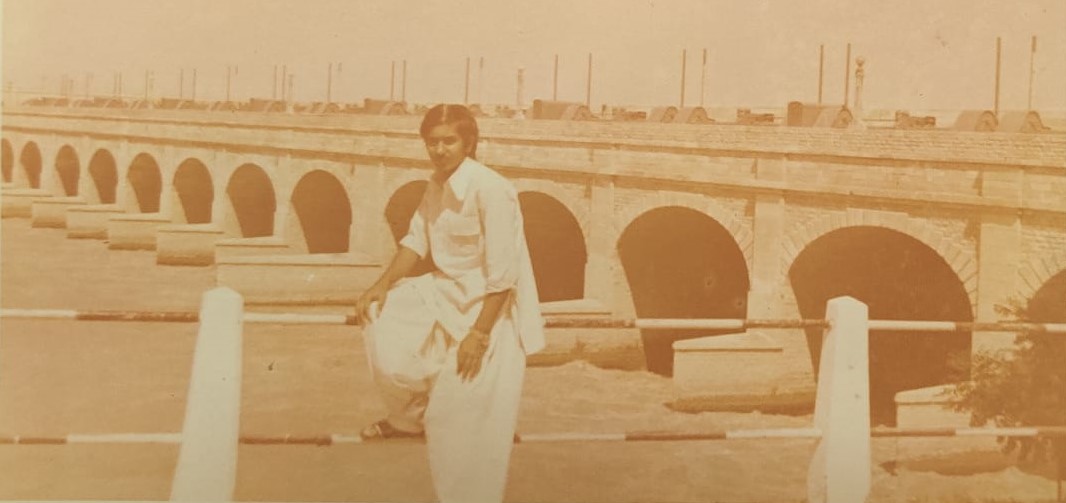

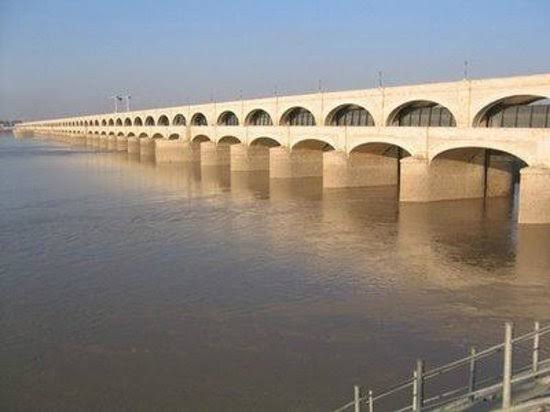

The Sukkur Barrage, built on river Sindhu by the British in 1932, is part of one of the world’s largest irrigation projects. Its many channels provide water both sides to the thriving agricultural farms in Sindh.

Both Lansdowne Bridge and Sukkur Barrage( Mr. Jagwani is posing in front of Sukkar Barrage) are architectural marvels of Sindh. Along with these two, Masoom Shah Jo Minaro, Ghanta Ghar, Sadhu Belo Zindah peer and Labe Mahran are some of the places worth seeing in Sukkur.

PIC CREDIT: MRS. SHAGUFTA SHAIKH, SEOUL, KOREA

THE TALK WITH Mr. SANTOSH JAGWANI

“I feel Sindhis in rural areas should have stayed back in Sindh. I wonder why Hindu Sindhis left Sindh when we were a powerful community. Most of the looting and plundering took place in cities of Karachi, Hyderabad, Shikarpur, Sukkur, etc; the villages were safe. If Hindu Sindhis had stayed back, our mithri (sweet) Sindh would have been with us.

The Sindhi Hindus living in Sindh today are surviving due to the love and support of the local Sindhi Muslim friends. Most of the Muslims of Sindh have a lot of huubh (love and affection) for Hindus. The Sindhi Hindus and Muslims, on the whole, live in harmony with each other.

The Hindus are lovingly called Diwan by the locals. Most Hindus are businessmen that trade in grains, dry fruits and textiles . Many have ginning factories as a lot of cotton grows in Sindh.”

HIS FAMILY IN SUKKAR

“Our ancestors lived at a village Phararo near Salephat in Sukkur District . We later moved to Januji, a few kilometers away from the city of Sukkur.

We had huge tracts of lands under farming and the major income of the family was from agricultural produce.

Before the Sukkur Barrage was built the land on eastern side of Sukkur district received water from Nara canal of the river Sindhu which flowed from Sukkur to Nara . When the Sindhu river got flooded, the Nara canal in turn had a lot of water for the farms.

In 1932, after Sukkur Barrage was built by the British, our land that was at an elevation dried up. The Nara canal water now flowed at a much lower level. Agriculture was not possible on our land any longer.

The family started a pumping station at the canal, supplying waters to the fields around my father and uncles started practising Unani medicines along with manufacturing Unani formulation, they earned good name as Unani Doctors.

Post partition, the family came to Trimonh (Kandhara), near Sukkur, and started a cotton ginning factory – separating cotton from seeds, at Begmaji village close by. They had a captive thermal power plant for the industry, supplying electricity to their factory. They started a ginning factory in Begmaji , Khairpur and other places with Hindu and Muslim partners.

They then shifted base to Sukkur and expanded cotton ginning work at other places in Sindh . My father stayed in Karachi as it was the capital of Sindh and a hub for textile and exports. The family stayed back in Sukkur.

But my father always yearned to settle in India. In 1962, my family started migrating to India. My maternal uncles, Shewaram Sugnomal Makhija, had already shifted to India after partition and ran a well- established cloth business in Revadi Bazar Ahmedabad. With their support, we started business here in 1968. By 1976, most of the family had settled in India, with my father shifting in 1979. Now we have my father’s cousins living in Sindh.

HIS EDUCATION

“In my time, there were two universities in Sindh: Karachi University and Sindh University Hyderabad . Now 8 to 10 different universities have come up. I did my matric education (9-10th board) from Sindh Board in Hyderabad. I continued my education in India, had to repeat the 10th board, and completed my Engineering degree here. We, 25 cousins, completed our preliminary and middle school in Sukkur but did our graduation In Ahmedabad, India .

My father and his brother were Unani doctors, so the family was always keen that we cousins received a quality education. We went on to study medicine or engineering. One of us went on to become a lawyer too.”

FOOD IN SINDH

“The water of the river Sindhu has its own taste and properties. Food cooked in this water is flavoursome and makes the people from Sindh robust and healthy with glowing skin.

I like all foods made here. Indian Sindhis make vegetarian food better and have a wider variety of vegetarian dishes.

In Sindh, there is a large repertoire of non-vegetarian food like fish, chicken, and mutton cooked in various ways. Prawns are available in Karachi, but not in Central Sindh.

The pallo fish (hilsa or illisha fish) of the Sindhu river we ate in Sindh is not available here. Spawned in Hyderabad, it swims upstream and becomes an adult pallo when it reaches Sukkur. Nare ji machhi (pallo fish from the Nara canal) is famous for its flavour. Macchi (fish)was made in gravy, tandoori, or fried. During breeding time, we get aani (roe) of pallo which is very tasty. Aani is fried, cut into pieces, and put in the gravy.

Ghosht (meat) of deer and partridge was popular in earlier days of Sindhi.

Bhugal teevan (mutton cooked in an onion based gravy), bhee and teevan ( lotus stem and mutton cooked together), bhugal chawaran (rice made in onion browned to perfection), and tayri (sweet rice with dry fruits) were often made at my place during family gatherings.

Keemo-kaleji (minced mutton and liver in onion- based gravy) is my absolute favourite dish.

Street vendors sold dal pakwan in Hindu Sindhi areas like Siru Chowk and Dharamshalla near Ghanta Ghar .

Lots of non-vegetarian variety such as mutton and chicken tikka, mutton and chicken in gravy are sold by vendors at street corners.”

CLOTHES OF SINDH

Suthan (loose palazzo like pants) and kurtas were worn by women. They also wore a nath (a ruby stone nose ring pierced through the septum of the nose).

Men wore a salwar and a long shirt. A topi (cap) or a pagh (turban) was worn as a sign of respect. Now, Sindhi topi and ajrakh (intricate hand-printed textile) are emblems of Sindh.

FURNITURE OF SINDH

The Sindh pingas (swings) were big enough to sleep. Two adults could easily fit in them. Made of wood and enclosed on all four sides, these swings were carved and decorated with mirrors and photographs of gods and goddesses.

An iron tijori (a safe) for jewellery in the house was a must.

Khat (stringed beds) with beautifully carved legs were used.

Sandhal (a wooden platform on legs) acted as a day bed for eating and sitting/sleeping.

Our houses in Sukkur had mungh – a big metal ventilation channel that ran from the terrace to the rooms downstairs and gave light and air to the house. These mungh could be opened and closed according to the season. People sleeping on the terrace could communicate through the mungh with the family in the house. Mungh were popular in houses of Hyderabad too.

LIFE IN VILLAGES

Life in villages in Sindh was relaxed. Many businesses such as cotton ginning factories or trading in dates run only for six months. People were free for the rest of the months. In the evening, they gathered on the otaak (a room outside the house where guests are received) in the neighbourhood where gilm (thick carpets) were spread and people smoked chillum together.

Elderly women sat around gossiping and smoked bidis or hookahs.

People are fond of naas (snuff powder) and there are huge shops dedicated to selling a variety of naas.”

MEMORIES OF SUKKUR

“There are so many memories of Sukkur –The Ghanta Ghar where everyone went to eat street food, our school that was opposite Mausam Shah Jo Minaro, the Sukkar Barrage we went to in the evening to have Abdulla’s ice cream.

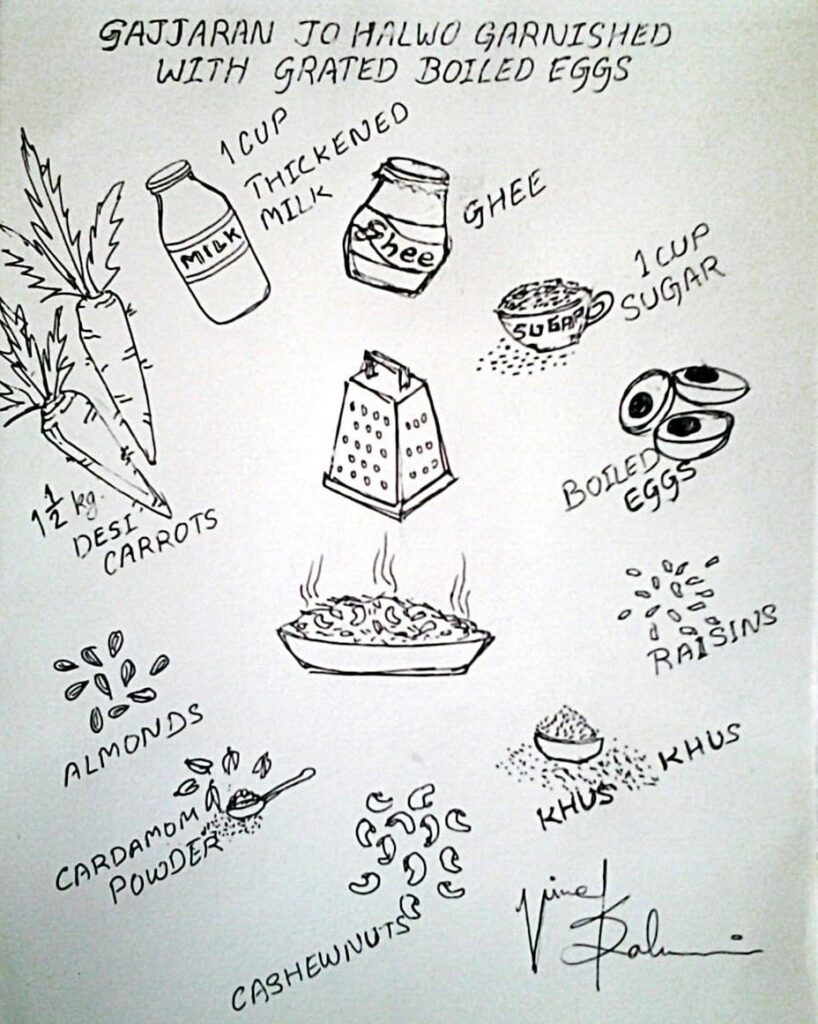

We ate falooda kulfi and gajjaran jo halwo (carrot halwa) at Ghanta Ghar. The vendors grated boiled eggs as a garnish on the halwo before serving.

Whenever we went to tikanna (a Sindhi temple that has Hindu Gods, Jhulelal and Guru Nanak, a perfect example of the syncretic faith that Sindhis follow) to worship (tikanne mein matho taken) on Chand (the auspicious new moon day of every lunar month), we had boiled eggs outside the tikanna.”

PIC: GAJJRAN JO HALWO GARNISHED WITH GRATED BOILED EGGS AT GHANTA GHAR, SUKKUR

ILLUSTRATION BY VIVEK DALWANI, MUMBAI

SADH BELO

(My Notes on Sadh Belo – Baba Bankhandi Maharaj, an Udasi ascetic, settled on an island in the Sindhu river near Sukkur in 1823 and the place is called Sadh Belo – the hermitage of a monk. The complex is spread over two interconnected islands and has temples dedicated to Annapurna Mata, Hanuman, Ganapati, and Shiv. Granth Sahib and Bhagavad Gita are placed here. Many prayers and religious texts are written and chanted in Sindhi.

The disciples of Baba Bankhandi, who like him follow the Udasi movement, are the priests at Sadh Belo. They now live in India and visit Sadh Belo every year to open the mela (a religious gathering) and attend it as the symbolic keepers of the Sadh Bela complex.

The Udasi movement was started by the eldest son of Guru Nanak, Sri Chand. It is a syncretic sect of Sikhism and Hinduism and advocates udasi – detachment, an indifference towards worldly concerns. The followers interpret Guru Nanak’s message in Vedantic terms and worship the Hindu deities as well the Guru Granth Saheb.)

“Sadh Belo is an island in the River Sindhu between Rohri and Sukkur. It is the biggest Udasi shrine in Pakistan, sacred to both, Hindus and Sikhs. It is very well maintained even today. Security is very tight and only Hindus and Sikhs are allowed to visit it. People of other faiths are not allowed as such except maybe if they are dignitaries. Earlier it had many entry points, but now there is only one from Sukkur for security purposes.

Sadh Belo has gardens, 9 temples, a library, and places for devotees to stay.

PIC : SADH BELO

We went to Sadh Belo in a boat every Friday evening. The flow of the river Sindhu here is very fast. Sukkur Barrage and Lansdowne Bridge, both made by the British, are on its either side.

The Muslim boatmen called muhanas take the boat in the middle of the river Sindhu (vich seer te) and sprinkle the water of river Sindhu (chhando)on the passengers. Pregnant women visit the river Sindhu at least once during their period of pregnancy for the chhando.

We received dodo (flatbread made of jowar flour) and chutney as prasad at Sadh Belo.

A mela is organised here annually on the anniversary of Baba Bankhandi. Devotees from all over Sindh, even from across the border, visit and are provided free food and lodging.

Preparations for the mela start a month ahead. Volunteers (sevadharis) stay on the island and help in the arrangements. My father too was an active volunteer. My mother woke up at five in the morning and made 100-200 fulkas (wheat flour rotis). She sent me with these together with home-made butter and lassi (buttermilk) in a pot for the volunteers.”

MELAS IN SINDH

There are more than a hundred thousand Hindu and Muslim saints that the people of Sindh have faith in. Many melas are held in memory of some of these saints.

Apart from Sadh Belo mela, we had Diwali mela, Kartakan jo Melo and a mela at Jhulelal (the River God – a form of Varun Devta) temple in Hyderabad.

Many people of Sindh believe in Sufism. Sufi saint Mast Qalandar or Shah Baaz qalander is worshipped by devotees at Shewan. An annual Urs ( death anniversary) is held at his shrine. The famous song, “Jhule Jhule Jhulelal Dum Mast Qalander” actually refers to him. After his death, Hindu Sindhis began to identify him with Jhulelal, the reference to which is made in the song.

HO JAMALO

“When Lansdowne Bridge was built by the British, they needed to run a train on it to test the strength of the bridge. Jamalo, a Muslim Siddi prisoner (Siddis were from Africa settled in Sindh), volunteered to do so, on the condition that he be released after he had completed the feat. His condition was accepted, he ran the train successfully and he was granted freedom. His wife, in celebration of his release, is believed to have sung the song, “Ho Jamalo….”. Today, no Sindhi can stop himself from dancing at this jubilant song.”

One of the favourite recipes of Mr. Santosh Jagwani is Keema Kaleji, a delicious combination of minced meat and liver cooked in a spicy masala. Like most Sindhi dishes, keema kaleji is cooked with a simple set of ingredients and spices to yield a finger-licking dish.

Here is its recipe given by his wife, Mrs. Meena Jagwani. She insists that the mixture while cooking should be sauteed well at each step as that’s what releases the flavour of the spices and imparts a rich colour to the dish.

KEEMA KALEJI (minced meat and liver in an onion-based gravy)

Serves 2

Ingredients

- Liver 200 gm

- Mutton Keema 300 gm

- 2 medium onions – finely chopped

- 4 Tomatoes – finely chopped

- 3 – 4 Green Chillies – chopped

- Ginger- Garlic Paste 1 tbsp

- Green Cardamom 3-4

- Cloves 4-5

- Cinnamon Stick 1 inch

- Mace (Javitri) 1 tsp

- Cumin Seeds 1 tbsp

- Pepper Powder 1 tsp

- Shahi Jeera (Caraway Seeds) ½ tsp

- Coriander Powder 2 tbsp

- Kashmiri Chilli Powder 2 tsp

- Turmeric Powder ½ tsp

- Garam Masala 1 tsp

- Bay leaf 2

- Salt to taste

- Curds 1 tbsp

- Ghee 2 tbsp

- Cooking Oil 2tbsp

- Freshly chopped coriander leaves for garnishing

Method

- Soak kaleji in water for 20 minutes as it helps to remove impurities. Drain the water and wash the liver pieces well. Chop it into pieces.

- Marinate minced meat and chopped liver in the marinade made of ginger- garlic paste, chillies, cumin seeds, cardamom, mace, cinnamon, and cloves ground together, curds, coriander powder, red chilli powder, pepper powder, and salt.

- Heat oil and ghee in a pressure cooker. Add caraway seeds and bay leaf and fry for a few seconds.

- Add onions and fry till brown. Add the marinated keema kaleji and saute.

- Add chopped tomatoes and fry for a few minutes.

- Add 1 cup water and cover the lid of the cooker.

- Cook for one whistle on high heat and then for 10 minutes on low heat.

- Open the lid after the pressure is released. Fry again till oil separates and the mixture gets a rich brown colour. Keep on stirring while doing so. Adjust the water if required.

- Garnish with fresh coriander leaves. Serve with fresh pav or fulkas.

Five Facts about Sindh and Sindhis:

- Sindhu river, before it enters Sindh, swells to a size bigger than Ganga, as the rivers Sutlej, Beas, Ravi, Chenab, Jhelum, and Zanskar pour their waters into it.

- The Sindhi dialect changes every few kilometers in Sindh. Hyderabad, Shikarpur, Sukkar, Larkana, Sant Kanwar Ram – each place has its own dialect. Mirpur Khas is closer to Gujarat and its Sindhi has a touch of Gujarati.

- River Sindhu has three important barrages on it- one as it enters Sindh, the other at Sukkur, and another at Hyderabad. These barrages irrigate Sindh, helping agriculture thrive in the region.

- Sukkur is the third biggest city in Sindh after Karachi and Hyderabad.

- Sindhis traditionally ate in vessels made of kut – an alloy of copper, which had to be coated with tin through a process called Kalai. Street vendors or artisans went from door-to-door offering their service to coat the vessels.

A personal account of Mr. Santosh Jagwani

Keema Kaleji recipe by Mrs. Meena Jagwani

Featured Image: Mr. Satosh Jagwani posing in front of Sukkur Bridge

Photo Credit:Personal Collection of Mr. Santosh Jagwani

Jyoti Mulchandani

Ahmedabad

Pingback:Memoirs of a Sindhi from Sukkur

thank you for this, never been there but I learned a lot about my heritage

Nostalgia

Send me more info on rural Sindh